How a quiet green deal between farmers and conservationists is saving Maharashtra’s Western Ghats | Pune News

Community participation and innovation can be key to protecting biodiversity. On World Environment Day , a look at how two friends from Pune found a way to conserve privately owned forests in Maharashtra by inking agreements with farmers.Five years ago, Rakshabai Ratate, a resident of Mandangad tehsil in Ratnagiri, finally managed to rebuild her dilapidated house, a project that had become long overdue because she could never seem to save up for it. The 78-year-old was able to finally undertake the project after she received some money in exchange for agreeing to protect her small patch of forested land in the foothills of the Western Ghats in Maharashtra’s Konkan belt.Ratate was keeping her side of a bargain she struck with Pune-based duo of Archana Godbole and Jayant Sarnaik, in which she agreed to not let anyone — including herself — chop down any tree in her private forest, promising to conserve the rich natural resources contained within.

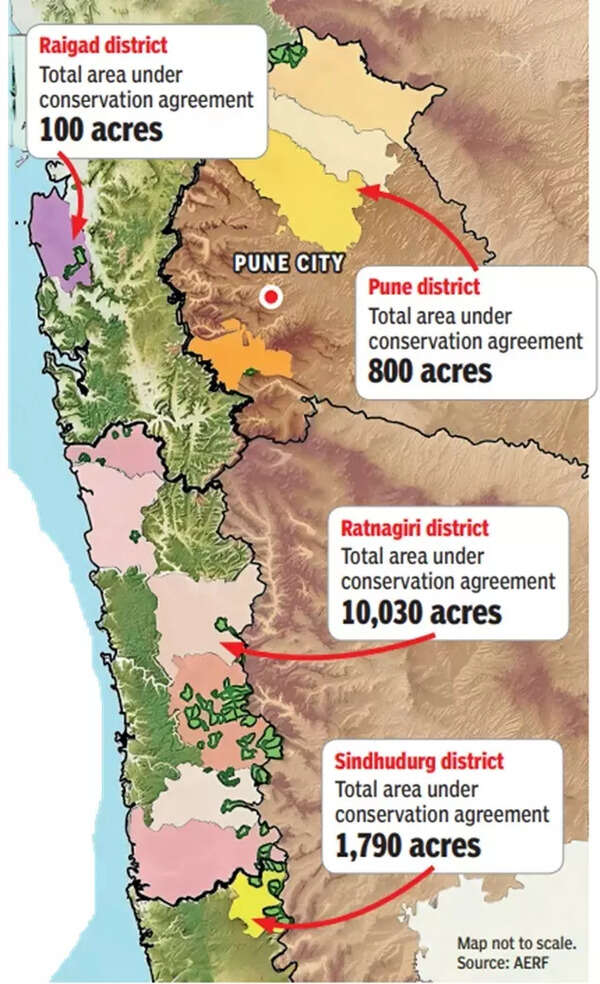

Like Ratate, hundreds of owners of private forested land in this part of the country have made — and kept — similar promises for years, building not only a special bond with Godbole and Sarnaik, but also with the land itself.Godbole, a plant taxonomist, and Sarnaik, a conservationist, are close friends from Pune who united for a dream: to protect the country’s green cover. In 1995, they founded the NGO Applied Environmental Research Foundation (AERF) to make their vision come true. For the last three decades, they have been working to conserve biodiversity with community participation and collaboration — from the people who own the land.Today, their dream — which started with 100 acres of protected forest as they launched the ‘Conservation Agreement’ movement in 2007-2008 — safeguards 13,000 acres of private forest land in the northern Western Ghats. Their journey began with a simple, though radical, idea: pay farmers and tribal landowners slightly more than what they would get from selling forest timber, in exchange for preserving their forests.Their mission, when it started out 17 years ago, seemed an impossible one. But the green cover continues to grow, one agreement at a time — thanks to the foundation’s community-based conservation model.And it all begins with a vow to protect and preserve.Green promises to keepTOI travelled with a team from AERF to Harihareshwar and Mandangad on the Konkan coast. The scale of this grassroots effort soon became apparent. An agreement signing takes just a few minutes — with a handshake and a signature — but what leads up to that moment is weeks, sometimes months, of groundwork.

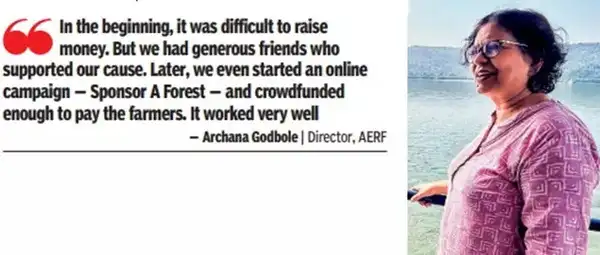

Godbole, Sarnaik and their team of field coordinators identify private forest land at risk of degradation, mostly in Ratnagiri and Sindhudurg districts. After a series of awareness meetings, which includes patient persuasion, the landowners — often poor farmers or members of tribal communities — sign a five-year legal conservation agreement. They are assured that their land will remain their own, while they are paid small, periodic instalments over the duration of the agreement. In return, the forests stay untouched.“In the beginning, it was difficult to raise money,” Godbole says. “But we had generous friends who supported our cause. Later, we even started an online campaign — ‘Sponsor A Forest’ — and crowdfunded enough resources to pay farmers. It worked very well.” But it wasn’t just about raising funds. Winning villagers’ trust was the bigger challenge.“Members of tribal communities and farmers do not have lucrative means, so they think of the forests as banks,” says Sarnaik. “They used to remove the forests to sell it to a logging contractor and earn a short-term income. That was affecting biodiversity.”AERF field coordinators make multiple visits to villages, explaining why forests matter, why biodiversity needs to be protected and, most importantly, why signing a legal agreement wouldn’t take their land away. “It was extremely challenging, and still is,” says Sarnaik. “But the only difference now is that we understand the sentiment of the forest owners and know how to convince them. These agreements help protect biodiversity-rich forests on privately owned land and give tangible economic benefits to poor farmers.”Bhausaheb Ratambe, a farmer from Mandangad who owns 2.5 acres of land dotted with indigenous trees, says many like him have realised that they can earn a livelihood from the trees without cutting them down.“Earlier, contractors would arrive and chop down the trees, pay us and leave. We took the money and used that to run our households, not realising that we’d lost the trees forever. Now, we know the importance of conservation. We still earn from the forests through its fruits, their medicinal uses and get the right direction from AERF volunteers. More and more people from our community are taking this up and reaping the benefits,” he says.A question of trustAkshay Gawade, a field coordinator in Mandangad, says, “The people that we work with for saving forests are actually marginal farmers who have limited options for earning sustainable incomes. In the past, they used to go to the forest, collect a few things and sell them. Or they practised shifting cultivation and grew traditional crops by chopping down their own forests.”“However, when these farmers migrated, the practice stopped and, as a result, secondary forests started growing. Now, over the last 30 to 40 years, these forests have become very healthy. The forests still remain private and we have about 1.2 million hectares under private ownership in Maharashtra’s Sahyadri mountains.”When Gawade started working in Mandangad block, it was quite difficult for him to win the locals’ confidence and get them to sign the agreement. Their team took almost a year to earn the community’s trust. The coordinators used to go to the landowners and hold several discussions with them until they obtained the required permissions. “We did not sign any agreement for one year in one of the villages. But we did not give up. Once they were convinced that we were going to do something better for their village, there was no looking back. Within a year, in 2024, we signed agreements for around 600 acres of private mangrove area and terrestrial forest,” Gawade adds.Power of legal coverWith its dense canopy, rare flora and endemic wildlife, the northern Western Ghats are breathtaking. But forests on private lands in India have no legal protection. They are vulnerable to logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, and sale to real-estate developers. Godbole and Sarnaik knew that waiting for policy changes would take decades, by when much of the forest would be gone. So, they created a legal framework, backed by community consensus, trust, and modest payments that could offset the economic pressure to sell or exploit the land.“Conservation agreements help us secure the commitment of local communities for ensuring long-term conservation,” Sarnaik says. “These agreements help us achieve outcomes and provide a window of opportunity to develop sustainable models for managing biodiversity.”At the core of their success is a “conservation-on-the-ground” approach — a three-pillar strategy that combines scientific research, community awareness and real-time action. With a strong grassroots reporting mechanism and a team of dedicated local coordinators, AERF ensures monitoring and support doesn’t end with a signed agreement.“From helping farmers plant native species to discouraging harmful landuse practices, we work closely with communities to create a culture of conservation — not as charity or sacrifice, but as empowerment,” says field coordinator Omkar Pai of Alibaug.“A truly sustainable world is not possible in a biodiversity-poor environment,” Godbole says. “Conservation issues are complex, but solutions can be found through consistent implementation and community innovation. Longterm effort is the only way.”