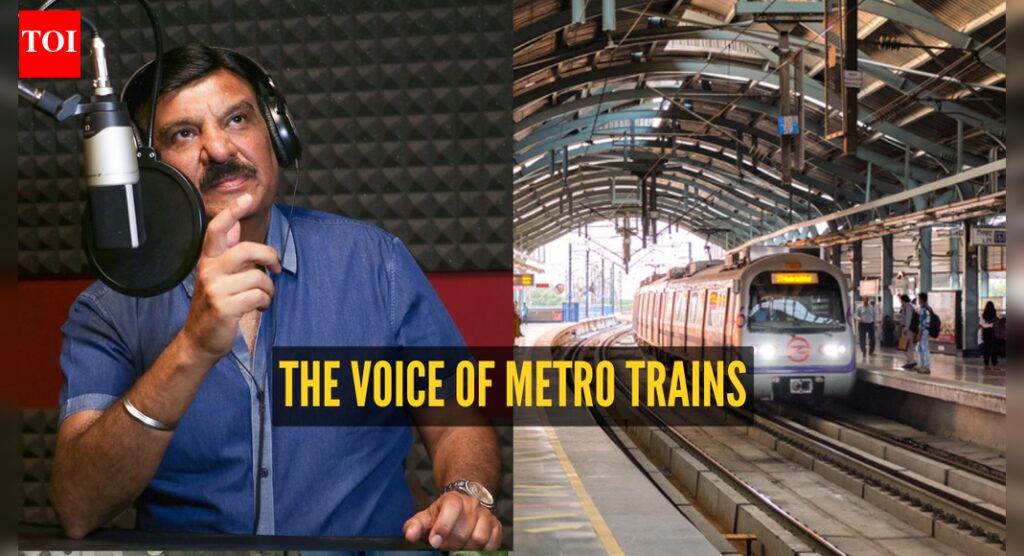

Shammi Narang: The man behind the metro voice

For millions of metro commuters in Delhi, the city’s rhythm is punctuated by a familiar, reassuring voice, one which is calm, precise and unmistakably authoritative. And that voice belongs to Shammi Narang, a name that predates the Delhi Metro. Long before metro announcements echoed through underground tunnels, Narang was already a household name thanks to his work with Doordarshan and iconic programmes like Gautam Darshan. So when the Delhi Metro Rail Corporation began its trial runs nearly two decades ago, his selection was both organic and inevitable.“It was both expected and a surprise,” Narang recalls. The DMRC, under the leadership of E. Sreedharan—fondly known as ‘Papa Metro’—initially viewed audio announcements as a technical requirement rather than a public-facing art. A short trial across seven or eight stations from Shahdara to Tis Hazari was planned, and the team needed a reliable voice to test the system. “They knew my voice. They trusted my credentials,” he says simply.Creating a Benchmark, One Pause at a TimeWhat neither the authorities nor Narang himself foresaw was the cultural impact those announcements would have. The now-iconic Metro cadence—with its deliberate pauses and crystal-clear diction, was not accidental, it was Narang’s professional instinct.“In a moving train, with track noise, crowds, distractions—you have to cut across,” he explains. “The pause was important. First the alert, then the message.” Initially, the style was questioned. “We don’t talk like this,” officials said. Narang countered, “No, we don’t—but this isn’t conversation. This is communication in chaos.”He recorded and submitted two versions: one conversational, another with his proposed structured pauses, along with a detailed explanation. The latter won. Today, that very style has become the standard across Metro systems in India, replicated city after city. “It became a benchmark,” he says, not with pride but quiet satisfaction.

Precision, Pronunciation and Public ResponsibilityFor Narang, the Metro announcements were never just about navigation—they were about language. “If you say Jor Baag, it has to be Baag, not Bag,” he emphasizes. Every dot, every inflection mattered. Children, students, daily commuters—millions would unconsciously learn pronunciation from these announcements. “We felt a responsibility. For ages, people had been mispronouncing names. This was a chance to correct that.”This perfectionism ensured that the DMRC never felt the need to experiment with variety. “They knew we wouldn’t mispronounce, wouldn’t compromise,” he says. Line by line, station by station, the voice stayed consistent—and history followed.

From Rashtrapati Bhavan to the Red FortThe Metro was just one chapter in Narang’s storied career. His voice has guided visitors through Rashtrapati Bhavan, the Red Fort, the Statue of Unity Museum, and countless light-and-sound shows across India. Each project, he says, demands a different discipline.“Rashtrapati Bhavan has its own decorum,” he explains. The influence of All India Radio stalwarts like Jasdev Singh and Melville de Mello still lingers. Government communication carries its own language politics—pure Hindi in some regions, Hindustani in others, English where required. “You must understand your target audience. Once you do that, no one doubts your credentials.”A Letter from the Prime Minister’s HouseOne of the most defining moments of Narang’s career came early, in the 1980s, during his Doordarshan days. Still a young newscaster reading low-power transmitter bulletins, he unexpectedly voiced a report on Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s tour. The modulation was minimal, the delivery natural.The next day, a letter arrived from the Prime Minister’s Office asking: Who did this voice-over? The directive followed—Shammi Narang would henceforth voice such reports. “That one voice-over changed everything,” he says. Soon came national bulletins, historic broadcasts, the turbulent days of 1984, and anchoring for successive Prime Ministers and Presidents. “There were no instant reactions then—only letters. But those letters meant everything.”

Voice, Discipline and the Future with AIAt an age when many slow down, Narang remains meticulous about his craft. “This is my bread and butter,” he says. He avoids smoking, excessive cold drinks, heavy indulgence—anything that might betray the voice that has defined him since his first Voice of America assignment in 1977.As for AI and synthetic voices, he is pragmatic, not fearful. “We shouldn’t be afraid of AI. We should be friends with it,” he says. Technology may generate sound, but experience shapes meaning. “Clarity, pronunciation, emotion—these come from lived understanding.”For young aspirants, his advice is simple yet profound: “Know your voice and don’t let the listener ask you to repeat yourself.” In an era of noise, Shammi Narang’s journey proves that a disciplined voice, used with intent, can move not just trains, but generations.