How Bihar’s ballot carries the weight of a 2,500-year democratic legacy

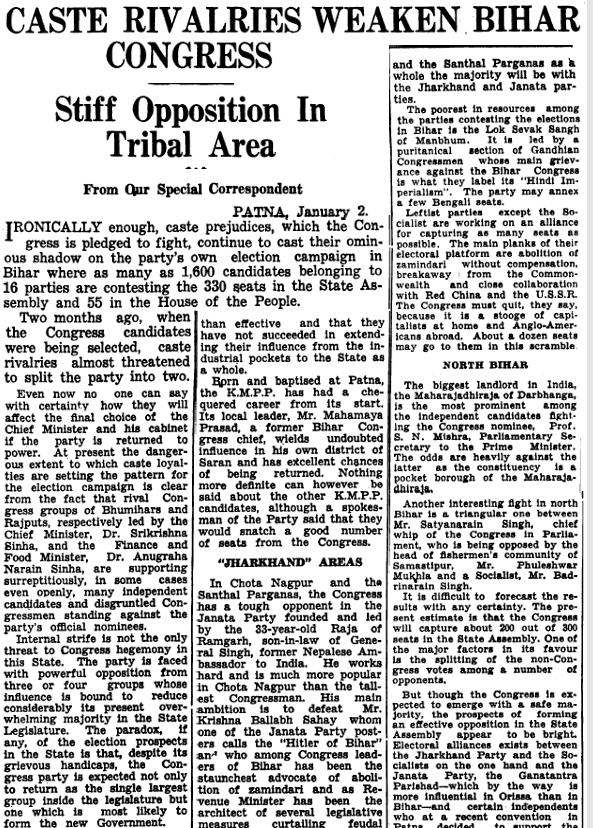

Morning of the first voteThe Election Commission’s official report lists 1,18,29,172 registered voters and 58,86,551 valid votes, a turnout just under 50 percent. For a largely agrarian province where literacy hovered around 20 percent, it was a striking debut.But the new machinery creaked. Names went missing from rolls, among them, the District Magistrate of Patna and even the Regional Election Commissioner and his wife. “No prior publicity had been given to booth allocations,” ToI observed. Yet the mood was festive; Patna, Gaya and Jamshedpur saw heavy turnout.Women participated in small but symbolically powerful numbers: 55 contested, 14 won, becoming among India’s earliest women legislators.On January 2, 1952, The Times of India warned under the headline “Caste Rivalries Weaken Bihar Congress.” The party that had led the freedom movement was now battling its own social divides. Chief Minister Srikrishna Sinha, a Bhumihar, and Finance Minister Anugraha Narain Sinha, a Rajput, covertly promoted candidates from their communities.In all, 1,600 candidates from 16 parties contested 330 Assembly and 55 Lok Sabha seats. The Congress campaign lacked ideological coherence, local loyalties and caste arithmetic overshadowed policy. Yet, for many voters, the word “Congress” still meant the nation itself.The same report also noted that caste prejudices the party was “pledged to fight” had instead “cast their ominous shadow” on its own ticket distribution.In Chota Nagpur and the Santhal Parganas, a new assertion took shape. The Jharkhand Party, led by Oxford-educated Jaipal Singh Munda, and the Janata Party of the Raja of Ramgarh, turned regional neglect into a demand for autonomy. Their slogan—“Our forests, our minerals, our government”—spoke to a population that mined coal and iron but lived in poverty.Rallies featured drums, tribal dances, and the party’s live-chicken symbol. Congress accused its rivals of intimidation; the Raja retorted that Patna was using the police to suppress dissent. The seeds of a future state, Jharkhand (born 2000), were sown in that contest.

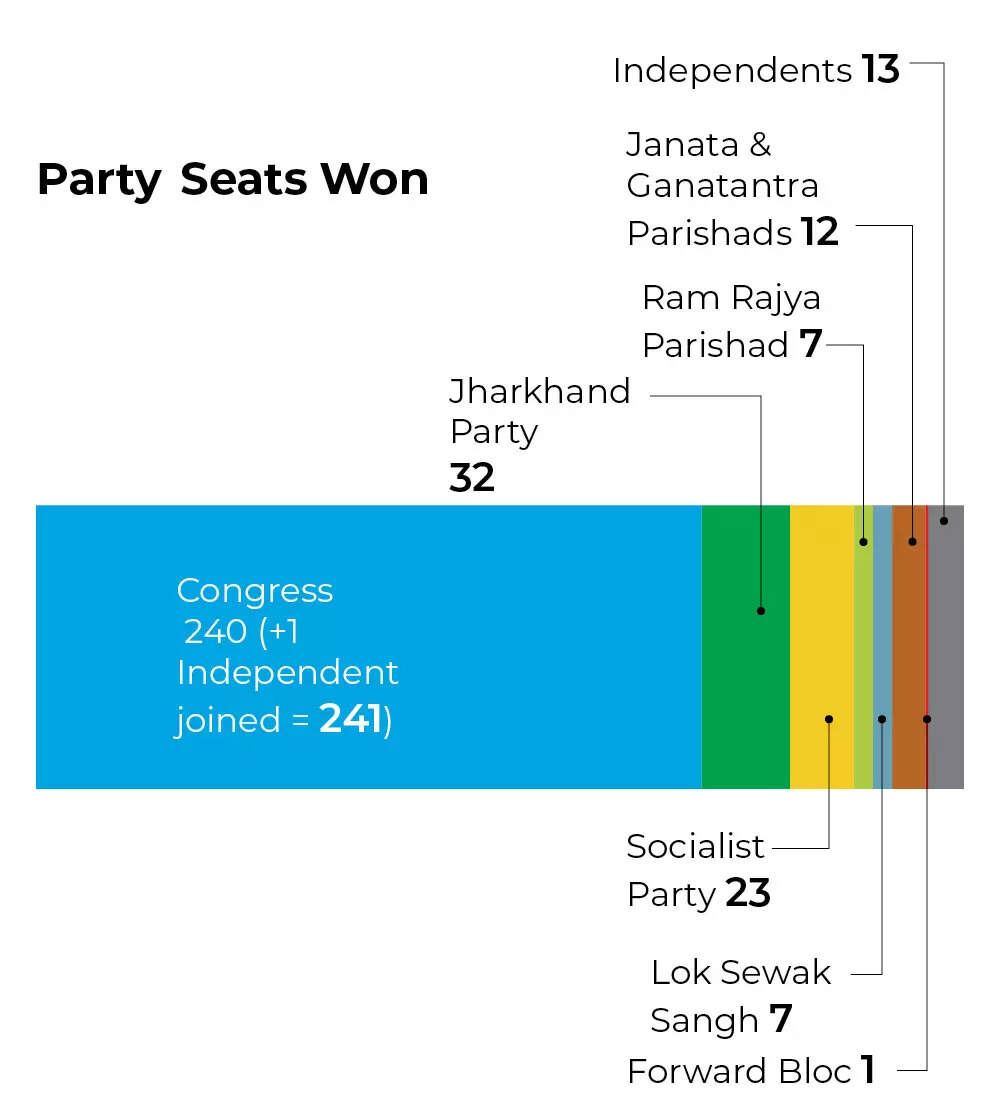

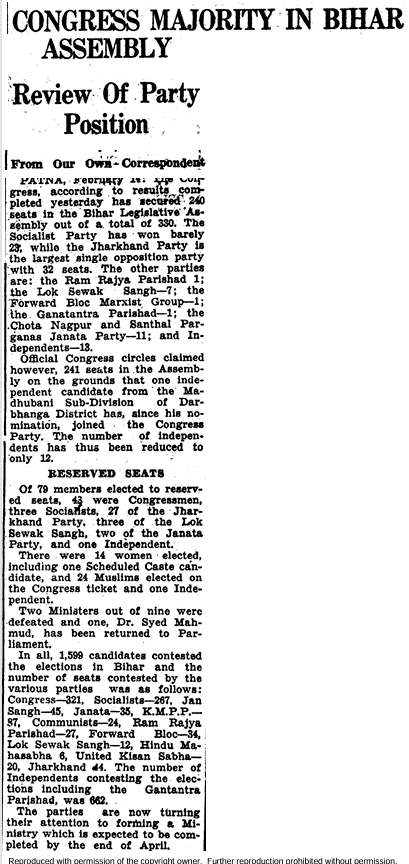

Verdict of 1952When counting ended in mid-February, The Times of India’s Feb 17 headline read “Congress Majority in Bihar Assembly.”

Of 79 reserved constituencies (47 SC + 32 ST), Congress won 43. The House included 14 women and 25 Muslim members.The Congress retained power with Dr Shri Krishna Sinha sworn in as the first elected Chief Minister under the Constitution, and Dr Anugraha Narain Sinha continuing as Deputy CM and Finance Minister.

What’s changed todaySeventy-three years later, the theatre has changed but the themes endure. The 2025 Assembly election, held in two phases (Nov 6 & 11), covers 243 seats, Bihar’s configuration after Jharkhand’s bifurcation in 2000.According to the Election Commission of India, 8.2 crore voters are enrolled; turnout crossed 6%, the highest in the state’s history. Women (71.6 %) again outnumbered men (62.8 %), a reversal from the early decades. The ECI’s SVEEP programme and a new cap of 1,200 voters per booth have added 13,000 polling stations, correcting the very gaps that dogged 1952.The ECI data show more than 3,500 candidates in fray, almost double the 2015 figure—proof that political participation, if not satisfaction, has only deepened.In 1952, the first Assembly fulfilled the Constitution’s promise of equality and participation. Today’s vote will measure whether those ideals can survive.